In January 1991, from the stage of the Maracana Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, George Michael, then 27 years old and among the most famous and successful pop stars in the world, spotted a handsome man in the crowd. Anselmo Feleppa would quickly become Michael’s lover, and his first real boyfriend. Soon they would be living together at the singer’s house in LA. By all accounts, not least Michael’s own, their affair was deep, passionate, and, at least at first, happy and carefree. Michael, who since adolescence had struggled with self-doubt, anxiety, and shame, felt he had finally met the man with whom he could share his life. Within months, Feleppa was unwell. Within a year of his first meeting with Michael he had been diagnosed as HIV positive and in 1993, aged 36, he died from an AIDS-related illness.

Heartbroken, Michael, an icon of red-blooded masculine sex appeal — “every single hungry schoolgirl’s pride and joy” — whose homosexuality was a tightly guarded secret at a time when to be openly gay was considered potentially ruinous to the career of an entertainer, did not fly to be at Feleppa’s side in his final moments. He did not attend the funeral. He mourned in private. In public, he threw himself into a legal battle with Sony, his record company, which he lost. He didn’t write a note for two years.

Finally, in the basement of a studio in west London, with new record deals in place, he began to write about awful events of the past few years. The songs became an album, Older, Michael’s third solo effort, released in 1996. It would produce an unprecedented six top three singles in the UK, where it became Michael’s biggest selling album, and it helped confirm his reputation as a writer and performer of supreme accomplishment.

But for all its success, and critical acclaim, especially here and in Europe, it could not compete commercially with Michael’s previous albums — few artists’ work ever could — and at the time it seemed an almost cussed change of direction for a singer-songwriter who, from his earliest days with Wham!, had always seemed in lockstep with the zeitgeist. Never again would that be the case.

Perhaps there could have been no propitious time to release a highly polished, slickly produced and utterly grief-stricken collection of sombre pop songs, expecting to repeat the global chart domination that George Michael had known — it would be incorrect to say “enjoyed” — earlier in his career. If there was a time, the summer of 1996 probably wasn’t it. At home in the UK, George Michael’s most loyal market, Britpop was at its peak. Cheeky, ironic, bolshy young scamps in tracksuit tops played beery singalongs to gangs of lachrymose lager lads. Alongside Oasis and Blur, the pop charts had fallen hard for the Spice Girls, whose cartoonish girl power anthems were about as far from Older as that album was from “Wake Me Up Before You Go Go”. (The Spice Girls’ debut Number One, “Wannabe”, kept Michael’s “Spinning the Wheel” from the top spot.) Take That, the most successful British boyband since the Beatles, were on the way out, with their most vivid personalities, Robbie Williams and Gary Barlow, publicly auditioning for the position of “the new George Michael.” (Seldom one for subtlety, Williams’s first single was a cover of Michael’s floor-filler, “Freedom ’90”. He got the job.) In the US, the country George Michael had conquered in the 1980s, thuggish gangsta rap and lubricious R’n’B were the sounds of the moment.

The austerely packaged, anguished crooning of a melancholy English pop star was always likely to be a tough sell at a moment of unthinking hedonism. (To perhaps no one’s surprise, Older, released in May, did not become the soundtrack to the Euro ’96 football tournament, the following month.) Its author’s decision to return to the fray after his long layoff not as a bouffant blond sex machine in a biker jacket but with a brooding, monochrome new image, his hair in a severe, Mr Spock crop, with a Mephistophelean goatee, seemed equally heedless of contemporary tastes.

In America the album flopped and Michael would never again challenge for chart supremacy there. But everywhere else, against the odds, Older was a hit, and to the end Michael considered it his best work. Listening to it today, even as a fan of his earlier, more effervescent material, you can see his point. Older is a quietly devastating record. At least four of its songs stand up as classics: “Jesus to a Child”, as bold a lead single as any megastar ever attempted, a stately, seven-minute ballad absolutely saturated in grief; “Fastlove”, a funky love-letter to cruising, yet somehow still bereft (“I miss my baby”); “You Have Been Loved”, almost unlistenable in its sadness; and “Spinning the Wheel”, written from the point of view of a gay man in an open relationship in the shadow of HIV. (A point of view Michael understood intimately.)

“There is not one track on that album,” Michael said later, “that’s not about Anselmo, about the fear of getting AIDS.”

Recently, over drinks, a friend of mine remarked that of all the “dead ones”, as she indelicately put it, George Michael’s mortality was the hardest to accept. “It just feels wrong to think that he’s not around. You hear him all the time. He’s everywhere. And he was so young.”

I was planning to open this piece with the observation that, six years after his death, George Michael appears to be having a moment: the Older re-release; a documentary in cinemas over the summer, and on streaming services now; a major new biography recently published. But the truth is that in my house, and my life, and the lives of millions of others, George Michael has been having a moment since 1982. And even though he died in 2016, the moment goes on, with no end in sight.

My friend is correct that at 53 George Michael was far too young to die. But he was considerably older than, for example, Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse and the rest of what Kurt’s mother called “that stupid club.” They died at 27, at the zenith of their fame and success. George Michael faded away, his relevance, if not quite his popularity, eclipsed by younger performers. And even though his death was a shock, his many personal troubles had long overshadowed his achievements. When he died, he hadn’t released an album of original material in twelve years, nor performed in front of an audience in nearly five. He had battled depression, drug addictions, critical illness, and numerous arrests. His career had first stalled, then stopped. Sad to admit, but he had become a tragic figure, haunted and forlorn.

That is not how we will remember him. And lately a critical consensus denied him in life, when he was often disparaged, at least by the rockist guardians of the canon, as a bland commercial confection, a phenomenon of the Thatcherite 1980s, seems to have transformed into something more celebratory. Michael was loved by his public, here and elsewhere. Now we agree that he was a major talent, a singer with a wonderfully warm, seductive voice — as well as an infectious disco growl — and a lyricist who could conjure genuine emotion, cheerful as well as downcast, from even the most apparently unpromising material. (“Fun and sunshine, there’s enough for everyone.”)

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

The recent documentary Freedom Uncut, with direction credited to Michael himself and his long-time associate David Austin, could hardly be said to be unbiased. It is a star-studded effort, featuring contributions from musical collaborators including Mary J Blige, Nile Rogers and Stevie Wonder, plus an unlikely VIP room of friends and admirers in Ricky Gervais, Jean Paul Gaultier, Tracey Emin, James Corden, sundry supermodels, and Liam Gallagher. “Modern. Day. Elvis,” is the erstwhile Oasis frontman’s scene-stealing commentary on Michael’s appeal. (While Gervais desperately titters, the younger Gallagher’s contribution is respectful, and effortlessly funny.)

Freedom Uncut, which is an expanded version of a film first shown in 2017, focuses primarily on Michael’s imperial phase, from the mid-1980s to the turn of the century, with particular attention given to his legal wranglings, and the death of Anselmo. The sex and drugs and blue-eyed soul is — mostly — conspicuous by its absence.

A new hardback biography, George Michael: A Life, by James Gavin, fills in these gaps although, on reflection, I rather wish it hadn’t bothered. A joyless trudge through the very worst moments of Michael’s life and career, it has the unerring ability to locate the cloud in every silver lining. Some might argue that this was true of its subject, too, and maybe so, but still: the book really is an enervating slog. And while the documentary may lean too far towards hagiography, at least we get some of the man’s wit and charm, as well as his talent, particularly in the footage of his live performances.

In the film, Michael speaks of an early “desperate ambition to be famous and to be loved.” Almost as soon as he found fame, as a teenager, with Wham!, he discovered its limitations. “If I was looking for happiness, this was the wrong road.” Nevertheless, he took it. His moment of greatest professional triumph — 1987’s Faith — was a personal disaster. He was “terribly lonely.” And, in public at least, he was living a lie. The butch ladykiller with the aviator shades and the steel-tipped cowboy boots, his naked Japanese girlfriend writhing orgasmically in the video for “I Want Your Sex”, was a closeted gay man, unable to share his true emotions with his fans.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Alternately elated by his success and terrified of what he had unleashed, Michael determined to step away from the spotlight, though not from his recording career. His second solo album, Listen Without Prejudice Vol 1 — there was never to be a Vol 2 — was a plea to be taken seriously as a mature songwriter (“Sometimes the clothes do not make the man”) but he felt its chances to connect as widely as Faith had were undermined by Sony’s bungling of its marketing. (In return they cited his own reluctance to promote the record in the traditional ways, declining to appear on its cover or in videos for its singles, or to tour widely.)

In 1990, Frank Sinatra sent George Michael an open letter advising the younger singer to get over himself. “The tragedy of fame,” wrote Sinatra, “is when no one shows up and you’re singing to the cleaning lady in some empty joint that hasn’t seen a paying customer since St. Swithin’s Day.”

Not as far as George Michael was concerned, it wasn’t. Until the end of his life he would continue to feel straitjacketed by mainstream pop stardom. Hence “Freedom! ‘90” and the songs that would follow it, not least those on Older. It is customary here to point to the supposed irony that this man who sang so yearningly about finding freedom so clearly felt trapped. But there’s nothing ironic about it. Like the proverbial caged bird, it was precisely because he felt cornered that he was able to so sing so movingly about wanting to escape. And that is why so many empathise with him, and are moved by his songs.

Michael is far from the only megastar to have mined feelings of grief, guilt, anger and abandonment for chart-topping success (Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse were both pretty adroit at that, too) but rarely can suffering have been so hauntingly conveyed in a series of pop songs, as it is on Older.

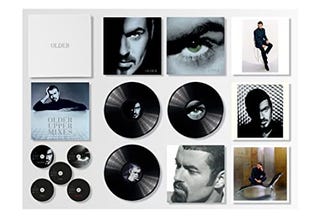

The new box set is a handsome item indeed. It’ll look smart on your shelf. And it’s nothing if not comprehensive, containing vinyl and CDs and a brochure and more remixes than a superstar DJ set. But my word, for all the catharsis of Older, for all Michael’s inspiring determination to move on from grief, to make something beautiful out of heartbreak, it is a sad and freighted document, too.

George Michael’s Older is released on 16 September, and available for pre-order now.

No comments:

Post a Comment