The members of Kikagaku Moyo remember setting many goals when they started the band a decade ago. They wanted to see the world and play psychedelic rock events such as the Austin Psych Fest.

“Then we realized we did pretty much everything we had wanted…actually more than what we were hoping for,” drummer Go Kurosawa says over video chat from his home in Amsterdam.

“So many American bands are like, ‘Grow, grow! Next! Just keep going, never stop and never end,’” guitarist Tomo Katsurada adds with a laugh from his place in the same city. “I find that so capitalistic. Why can’t you guys just end and do new stuff?”

That’s exactly what Kikagaku Moyo decided upon during recording their fifth and final album Kumoyo Island, released this past May via their own label Guruguru Brain. Over the past ten years, the quintet—Katsurada, Kurosawa, his brother Ryu, Kotsu Guy, and Daoud Popal—became global representatives of Tokyo’s underground rock landscape thanks to their penchant for never settling. They created smoky folk jams, slow-burning sitar epics, and chugging rock blowouts delivered under waves of feedback.

“We’ve felt like, yeah, we already did one thing. It’s natural for us to think, ‘OK, when we do this, let’s do something different,’” Kurosawa says.

The pair spoke to Bandcamp Daily days after wrapping up their final European tour, including a set at Glastonbury Festival’s West Holts stage. “We were told we had the highest record sales in the history of that stage,” Katsurada says of the most special memory of this last jaunt across the continent, taking pride in how they managed that as a DIY operation.

“Our Amsterdam show…it felt like the European loop was closed,” Kurosawa says. “The first show we ever played in Europe was in the Netherlands; that’s how we started.”

Kikagaku Moyo still have a series of live shows in front of them ahead of their curtain-closing tour of North America this fall. After that, the band ends, and everyone can explore new avenues of expression. A well-deserved opportunity, as the band has created one of 21st-century psych rock’s strongest discographies.

Katsurada and Kurosawa met shortly after the former returned to Tokyo after studying abroad in Portland. “We had a lot of mutual friends from where Go was from…[Tokyo neighborhood] Takadanobaba…and I was studying at the nearby Waseda University,” he says. “I was in a skater crew made up of Go’s elementary and junior high school friends.” The two bonded over music, movies, and food, spending copious amounts of time hanging out.

“There’s not many Japanese people we found who could communicate with the outside world. The language barrier is such a thing, and if you don’t experience living outside of Japan, the world looks really closed,” Katsurada says. “Like, I have to do everything in Japan. But there’s so many options, and we talked about all of our ideas.”

The two found they had good energy and decided to give music a try. The only hitch, Kurosawa notes, is that neither of them really knew how to play any instruments. “I didn’t know how to play drums,” he says, while Katsurada compared their early days to “a high school opening band.”

They brought the other members into the band soon after and got to work playing live shows. Despite their self-professed lack of technique, they had lots of ideas and spent a lot of time simply jamming and figuring out what kind of sounds they wanted to make and how to approach singing. “We thought we didn’t have to sing lyrics specifically; we can use it as a melody or an instrument that includes a feeling,” Katsurada says, comparing it to growing up in Japan and listening to Missy Elliott despite understanding nothing she was saying.

“The first record we did was almost like a demo,” Kurosawa says of their 2013 titular debut. “We had opened for Moon Duo, and they told us to record something that we could give out to people. If you just play lots of shows, you won’t go anywhere.” The resulting release found them exploring sounds they would tinker with for the next decade, including speedy rock blazers (“Zo No Senaka”) and wisps of folk (“Lazy Stoned Monk”). Their relative lack of technical proficiency wasn’t a deterrent, but rather an asset allowing them to experiment freely.

They might have said they weren’t technically strong, but that only opened them up to further spread their sound.

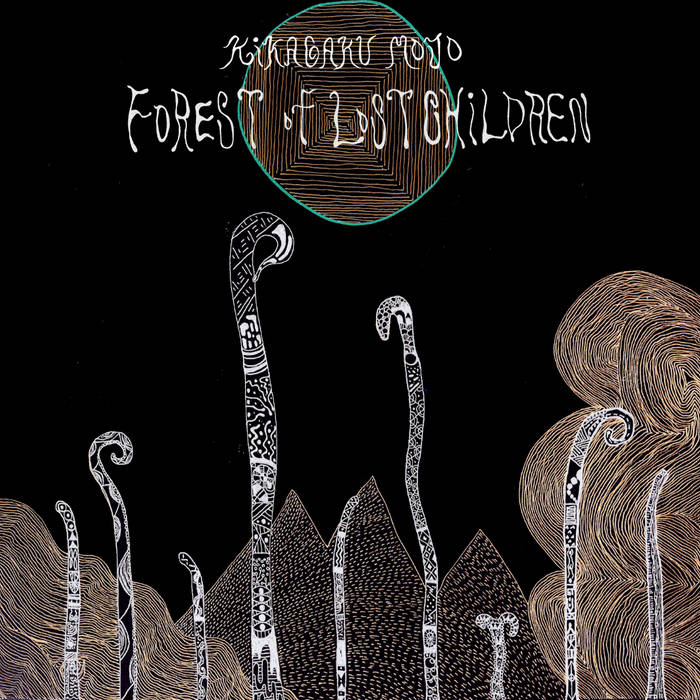

Forest Of Lost Children

Kikagaku Moyo continued playing live shows across Tokyo, focusing on smaller venues that didn’t stick to the pay-to-play model common in the country (with some busking thrown in). The five-piece wanted to start touring outside their home nation, though.

“We found out that we needed an album to tour internationally,” Katsurada says with a laugh, explaining how the second album, Forest Of Lost Children, came together. “It was us rushing.”

Despite the frantic pace required to put it together, their second full-length highlights both their conceptual drive and myriad global influences. “We wanted to make music that came from an imaginary tribal island, all these sounds mixed together. Like the stress of Calcutta with rural areas,” Katsurada says. Many were written around the time of their debut, but gelled together nicely on Forest, highlighted by the shapeshifting psych rocker “Smoke And Mirrors.”

A label expressed interest in their follow-up, and they excitedly sent it over. “All of them said ‘Nope. I don’t like it.’ And we lost the deal!” Katsurada says. Still hoping to make their international hopes a reality, they found a small label in New York, Beyond Beyond Is Beyond Records, to put it out. That helped them land dates in the United States, including an appearance at the 2014 edition of the Austin Psych Fest, one of their dream gigs. While still a niche band at home, Kikagaku Moyo were starting to make a name for themselves with their meditative and mind-bending music.

Whatever attention Kikagaku Moyo were getting was countered a bit by their continued frustration with labels. “With our third album, we were really looking forward to getting signed with a record label, but nobody was interested in it,” Katsurada says of what would become House In The Tall Grass. “They’d say, ‘It’s not my cup of tea.’ I heard that so much over Facebook messenger. ‘It’s not my cup of tea; it’s not my cup of tea…”

“So we decided, let’s release it ourselves,” he concludes.

By 2016, Katsurada and Kurosawa had already launched their own label, Guruguru Brain. That emerged from a regular party they held at Shibuya’s Ruby Room venue. They decided to create a compilation album of psych acts playing the event, releasing that as the imprint’s first offering in 2014. It soon became a place where they could highlight music from Japanese psych rockers like SUNDAYS & CYBELE and the Krautrock-inspired Minami Deustch, along with groups from across Asia.

“When we started, it wasn’t for self releases, it was separate from our band,” Kurosawa says. “But when we couldn’t find a label, naturally, we decided to do it ourselves. We had no choice.”

House In The Tall Grass has become important to both of them. Kurosawa remembers the album’s creation—getting out of work, heading to a studio, creating it for two or three hours, and listening to rough mixes on the train home—better than any other.

“At that point, we finally started touring internationally more than ever before. That’s when we realized we could make the band financially stable for everybody, and we could do it without having to depend on another label. House In The Tall Grass was when we decided to do things by ourselves,” Katsurada says, noting he felt his songwriting grew alongside this recording.

This album marks the arrival of the internationally celebrated Kikagaku Moyo, free to do what they want without worrying about labels reacting to demos or anything else. “If the five members of the band feel it’s good, there’s no conversation needed after that. There’s no filter,” Kurosawa says. After this, the group released EPs, collaborations, and a full-length album all on their own terms.

Many of Kikagaku Moyo’s albums emerged from touring, with the members drawing inspiration from the jams and memories made on the road. The COVID-19 pandemic, though, cut off that creative pipeline.

“It’s all from our imagination, how we play together since we couldn’t tour,” Katsurada says. “Half of the songs, probably, were written remotely.”

Unlike previous albums, Kumoyo Island boasts what Kurosawa describes as a “home recording feeling,” owing to each member being able to take their time in writing due to limitations presented by the state of the world. “It was a good balance between the five of us having to imagine how these songs would sound together, but also allowing us to each experiment. I think it shows through.”

“But I’m happy that, in the end, it still sounded like a band sound,” Katsurada says. “We tour so much and play so many shows together; even when we are writing music at home, it becomes a band thing.”

They all returned to Tokyo for one month to finish the album, recording their finale at the same recording studio where they started, resulting in sessions that felt freer to the band than usual. “It was comfortable. We know the studio, we know the sound engineer, we can fuck it up, we can do trial and error,” Katsurada says.

Kumoyo Island is the band’s most left-field set of songs to date, merging their psych side with funk (“Dancing Blue”) and soothing soundscape (“Daydream Soda”). Musical periods from their entire time together emerge, from fuzzed-out rockers like “Cardboard Pile” to a sitar meditation on closer “Maison Silk Road.” Their Japanese roots even get a more prominent place on opener “Monaka,” which draws from minyo music that Katsurada says he frequently heard while growing up in a “not gorgeous” hot spring and ski resort in Ishikawa prefecture.

It’s a fitting swan song for the band and one Katsurada and Kurosawa are proud of, describing it as the album that means the most to them now.

After their final set of live dates, the pair will focus on Guruguru Brain, which has many releases set for the future (while also requiring them to handle all kinds of Kikagaku Moyo’s smaller details such as sending money to band members, due to them owning all their rights). They also will continue to make music, both by themselves and possibly together in new formations. But first, a few more goodbyes.

“I’m enjoying it a lot, being very emotional,” Katsurada says of the farewell tour. “It’s the best experience I’ve ever had playing music.”

No comments:

Post a Comment